The Maronite Liturgical Year

Sunday of the Church

Consecration of the Church Sunday

Dedication of the Church Sunday

Season of Announcement and Birth of our Lord

Announcement to Zechariah: First Sunday of Announcement Announcement to Mary: Second Sunday of Announcement Visitation to Elizabeth: Third Sunday of Announcement Birth of John the Baptizer: Fourth Sunday of Announcement Revelation to Joseph: Fifth Sunday of Announcement Genealogy Sunday: Sunday before the Birth of our Lord

Birth of our Lord

(First Sunday after the Birth of our Lord) Sunday of the Finding in the Temple

Season of Epiphany

Epiphany

First to Fifth Sundays of Epiphany

Sunday of Deceased Priests

Sunday of the Righteous and Just

Sunday of the Faithful Departed

Season of Great Lent

Cana Sunday: Entrance into Lent

Sunday of the Leper: Second Sunday of Lent

Sunday of the Hemorrhaging Woman: Third Sunday of Lent

Sunday of the Prodigal Son: Fourth Sunday of Lent

Sunday of the Paralytic: Fifth Sunday of Lent

Sunday of Bartimaeus the Blind: Sixth Sunday of Lent Hosanna Sunday

Passion Week

Monday of Passion Week

Tuesday of Passion Week

Wednesday of Passion Week

Thursday of Mysteries

Great Friday of the Crucifixion

Great Saturday of the Light

Seasons of Resurrection

Resurrection of our Lord

First Sunday of the Resurrection: New Sunday

Second to Fifth Sundays of the Resurrection

Ascension of our Lord: Ascension Thursday

Sixth Sunday of the Resurrection: Sunday after Ascension Pentecost

Season After Pentecost

First to Sixth Sundays after Pentecost

Season of the Holy Cross

Exaltation of the Holy Cross

First to fourteenth Sundays after Holy Cross

Maronite Rich Tradition

Maronite Rich Tradition

Written by Chorbishop Seely Beggiani, Rector Emeritus of Our Lady Of Lebanon Maronite Seminary, Washington, D.C.

To be a person of faith involves several dimensions. Religious faith is the conviction that all of reality, despite the many aspects of life that seem to go wrong, is radically good and has an ultimate purpose. Faith arises from an encounter where God offers us his unconditioned love and awaits our response. For the Christian, faith is the choice to see God, the world, and ourselves through the eyes of Jesus Christ, and the decision to live our lives according to His teachings and His way of life. Faith is embodied in liturgical worship, creeds, a code of morality, and commitments to action especially against injustice.

The Word of God is infinite and cannot be contained or exhausted in any one human culture or theology. Human beings respond to God’s Word in belief and worship that can only be expressed in finite ways. God intended that His plan of salvation be incarnated in a plurality of cultures and peoples. Thus, from the beginning, the preaching of the Gospel of Christ was articulated in various languages and explained through various cultural expressions. The faith response to this preaching was in the language, music, poetry, art, and architecture of the particular people to whom it was preached. In the first centuries of the Christian era, the Gospel of Christ became embodied in the cultures of the Middle and Far East, North Africa, Asia Minor and Europe. The various Church traditions throughout the world celebrate the richness of God’s Word and the human response to it. These Church traditions we identify as the Chaldean, Antiochene, Coptic, Byzantine, Armenian, and Roman traditions. No tradition is superior to the other. But the Church as a whole is diminished when one or more of these traditions are ignored.

It is likely that the Blessed Mother and the Apostles expressed their faith in Christ and worshipped in their Hebrew and Aramaic culture. What we refer to as Jewish Christianity spread to the east of Palestine to Mesopotamia, and north of Palestine to the regions east of Antioch. The liturgy that became crystallized in these regions constitutes the earliest liturgical tradition in the Church.

We are told by Theodoret, Bishop of Cyr, who wrote a Religious History, that among the holy hermits who lived in the region of Homs and Hama in Syria in the fourth century, there was a renowned person name Maron. Maron devoted his life to prayer and asceticism and to spiritual direction. He was known to have the gift of healing both of bodies and of souls. Maron himself did not found an? institution. However, after his death in the fifth century his followers established a monastery in his name which became the major monastery in the region. Its monks were staunch defenders of the teachings of the Church. The monks and the lay people associated with the monastery became known as the Maronites.

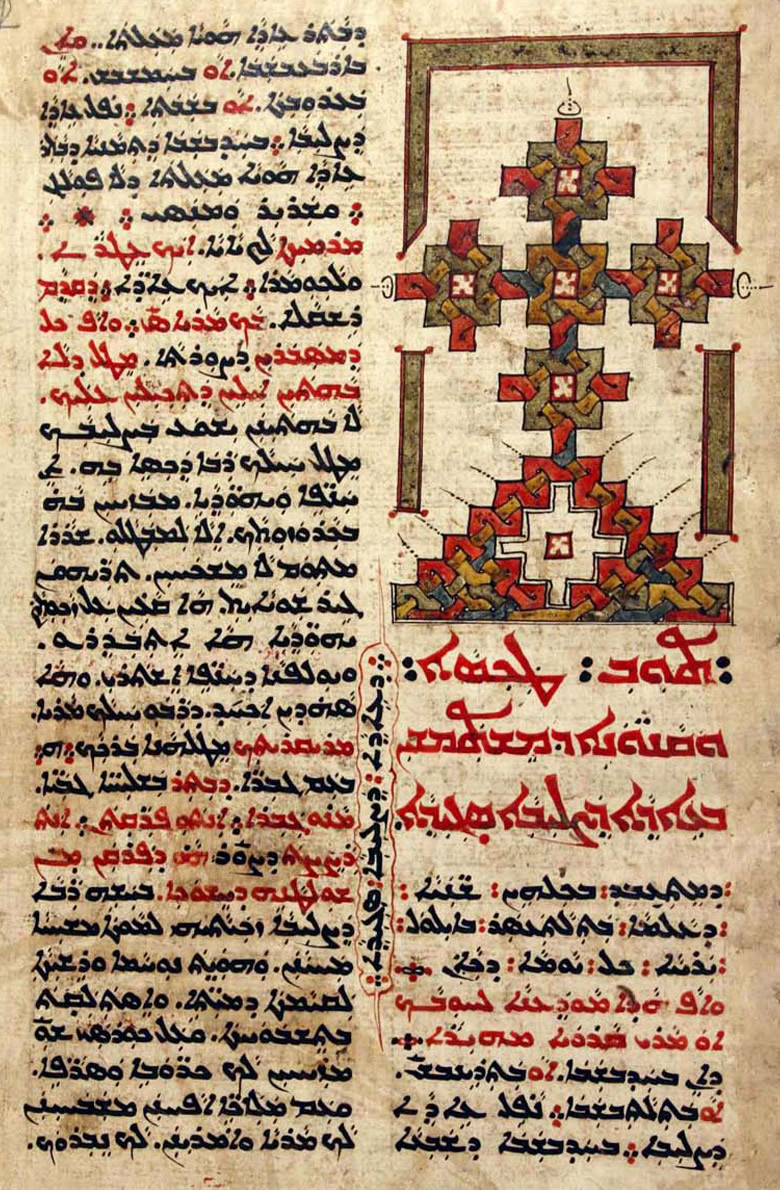

In their worship and liturgy, the Maronites reflected the tradition of Jewish Christianity. The theology found in their liturgy is that of St. Ephrem, one of the greatest Fathers of the Church. Their earliest Eucharistic Prayer (Anaphora), known as the Anaphora of Third Peter or Sharar, is the oldest in the Church and shares a common ancestry with the Chaldean Anaphora of Addai and Mari. Many of the liturgical prayers and the ritual of baptism can be traced to St. Ephrem and another great Syriac writer, James of Serug.

With the Arab invasions of the 7th century, the Maronite center of gravity moved to Lebanon. It was also in the latter half of the 7th century when the church of Antioch was in chaos that the Maronite Patriarchate of Antioch was established. Thus, the Maronites incorporated into their identity the theological and liturgical tradition of that famous city. Antioch had been the third largest city in the Roman Empire and a center of Hellenistic culture. It also was the site of a famous school of Christian theology and Scriptural interpretation. Because of the Antiochene influence, the Maronite liturgical tradition features a richness of Eucharistic prayers, including the Anaphora of the Twelve Apostles, which reflects the ancient anaphora of Antioch and which is the model for the Byzantine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom.

Since both the Liturgy and religious life are living realities, they are constantly being affected by the cultures in which they find themselves. Through its many centuries in Lebanon, the Maronite tradition has incorporated many hymns and paralitrugical practices and customs that reflect the Lebanese character. On the other hand, the Maronite values of freedom, independence, and human rights have had a profound impact on the formation of the Lebanese nation.

Maronites in the United States are bearers of a rich tradition. Not only do they embody their ethnic heritage, but they also witness to two great religious traditions, the tradition of the earliest converts to Christianity and the rich heritage of the Church of Antioch. Their prayers and liturgical formulas are filled with references to Sacred Scripture. Their hymns are filled with the poetry of the Middle East. Maronite theology emphasizes the mysteriousness of God, but also the call to humans to be united to divinity through the humanity of Christ. It declares that humans beings are not only created in the image and likeness of God, but are also called to a new creation through the Holy Spirit in baptism where they become spiritual beings called to immortality. It honors the Blessed Mother as being the New Eve and the paradigm of the Church.

The mission of Maronites in the United States is not only to preserve the Maronite way of life among themselves, but also to share their religious heritage with Catholics who belong to other Church tradition. It is only in this way that the whole Catholic Church can be enriched by all the various ways that humanity responds to the call of Christ. Maronites in the United States are also called to witness to their fellow Americans, their religious insights into the meaning of human existence, their high code of morality, their dedication to family, their natural hospitality, and their love of God’s creation. If the strength of the United States is to be found in the contributions of its peoples from all parts of the world, to be Maronite, to learn what it is to be Maronite and to share the Maronite lifestyle with others, not only fulfills our Christian vocation, but also serves to enhance the American character.

The Importance of Syriac

The Importance of Syriac

Fr. Armando ElKhoury

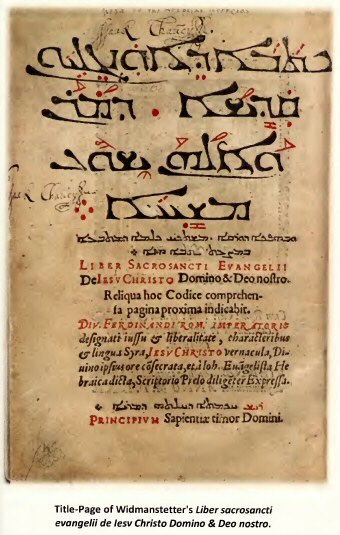

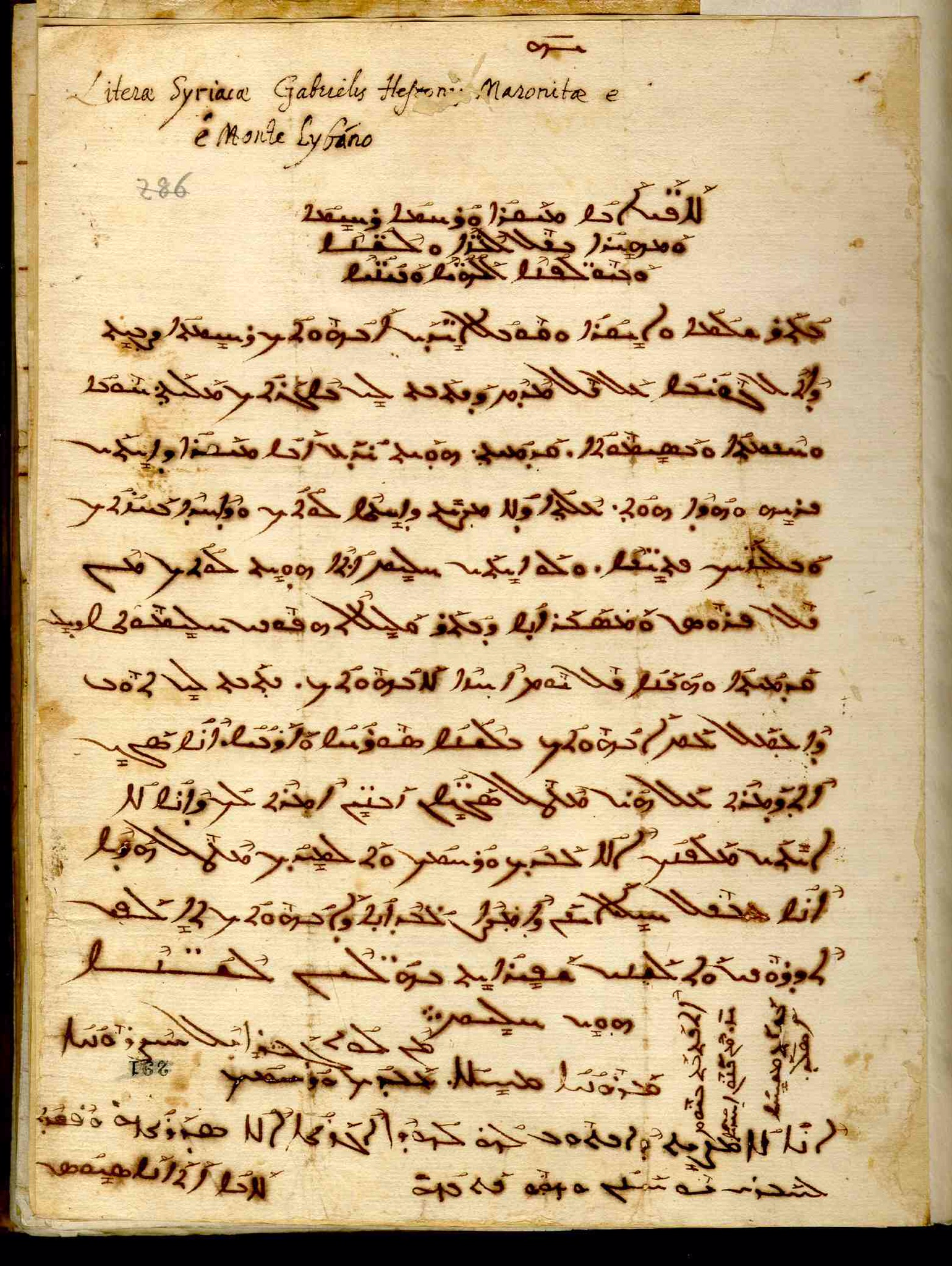

Aramaic, an ancient language spoken in the Near and Middle East, goes back to the 9th century BC. Like any language, it evolved with time and broke off into several dialects. Syriac (Suryoyo), one of these dialects that came to the scene decades after the Ascension of our Lord, became the dominant Christian literary language among the Peoples who spoke these various local Aramaic tongues and whose presence extended from the coast of present-day Lebanon all the way to China.

Almost a hundred years after the coming of Islam and the Arabs’ conquests, which started in the 7th century AD, the Aramaic dialects gave way to various “Arabic” dialects. Furthermore, classical Arabic became the official language of the burgeoning Islamic empire. The Syriac speaking Peoples eventually lost their ancestral language – the language was not totally extinguished, for it continues to be spoken nowadays, albeit in a modern form – and lost, consequently, a valuable key to their rich Christian heritage. Syriac theological giants, such as Aphrahat, the Persian Sage, Ephrem, the Harp of the Holy Spirit, and Jacob of Sarug, the Flute of the Holy Spirit, left behind spiritual, theological, and liturgical treasures locked in a vast treasury whose key is the Syriac language. A tiny portion of this wealth of writings has been translated into various modern languages and is, for the most part, inaccessible to a person who is not working in this field. These spiritual ancestors are our yet to be studied Augustines and Aquinases, yet to be exhibited Rembrandts and Picasos, yet to be heard Mozarts and Wagners, yet to be read Chaucers and Shakespeares, yet to be contemplated Platos and Aristotles, and yet to be translated Hugos and Dostojefskis. Syriac was the medium through which our unique Syriac theology was born and flourished. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for biblical studies, patristic studies, early Christianity and Syriac poetry. Moreover, it is an indispensable cultural bridge.1 To know Syriac is, therefore, to unearth the insights of our early Christian spiritual ancestors. An anonymous Syriac author wrote in the 5th century, “I [the Church] am like the pearl that was born under the water; the Holy Spirit descended and drew me up to place me on the King’s diadem. The Bridegroom alighted from His Father’s house to prepare the wedding feast for the Bride. In the womb of the font did He crown and make her resplendent and pure.” “Jesus is mine and I am His. He has desired me: He has clothed Himself in me, and I am clothed in Him. With the kisses of His mouth has He kissed me and brought me to His Bridal Chamber on high.”2 We, the Maronites, are not only heirs and custodians of these spiritual jewels which we share with the other Syriac Churches, but we have the responsibility to share this wealth with the world as well. What distinguishes the Antiochene Syriac Maronite Church from other Churches? It is precisely in these spiritual gold nuggets that the Maronite Church is distinguished from the other Churches. Distinguished does not, however, mean better. Rather, it allows us to recognize the uniqueness of the Maronite Church, the distinctive spiritual riches it carries and its vital role in inviting others to become members of the Body of Jesus the Messiah. A few Maronite Scholars in the United States such as Chorbishop Seely Beggiani understood this and have spent their time and energy sharing with us the Syriac theological worldview, which they cherish, through the education they acquired to instill in us a love for our Syriac tradition. To envision a world in which all Maronites would speak Syriac, or for that matter any other language, is in my humble opinion immaterial, for that should never be within the missionary scope of the Maronite Church. Nevertheless, to envision a world with numerous Maronite scholars in Syriac studies, who would bring these hidden pearls into our hands, is significant and attainable. Promoting Syriac studies and encouraging, fostering, and supporting Maronites who might choose this field of studies is, therefore, priceless. It is not a question of remaining in the past, but rather of studying it to continue building our distinctive Syriac theology on the shoulders of giants. Consequently, all would have unrestricted access to this vast treasury. 1 See Sebastian Brock, “Introduction to Syriac Studies,” in Horizons in Semitic Studies, ed. John Henry Eaton, University Semitic Study Aids; 8 (Birmingham: Dept. of Theology, Univ., 1980), 1–33. http://www.tertullian.org/rpearse/oriental/Brock_Introduction.pdf. 2 Sebastian Brock, “An Anonymous Hymn for Epiphany,” Parole de l’Orient, 15 (1989-1988): 175-176.

© copy right, Inc. All rights reserved.